Why We Buy Insurance and Play the Lottery

How Our Brains Distort Small Probabilities

This is The Curious Mind, by Álvaro Muñiz: a newsletter where you will learn about technical topics in an easy way, from decision-making to personal finance.

Why do we sometimes buy lottery tickets we know we’ll lose, and at other times pay for insurance we know will never “pay back”?

At first glance, these two behaviors seem opposite: one is chasing risk, the other is avoiding it. Yet both come from the same psychological quirk—how our minds perceive possibility.

This post explores how we assign value to money and uncertainty. Through a few simple examples, we’ll see why our attitude toward risk flips depending on whether we’re thinking about gains, losses, or unlikely events. And how the “possibility effect,” a key idea from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, quietly shapes decisions we make every day.

Money vs. Utility

We have talked about utility several times in this newsletter.

If you haven’t read those posts, here’s a quick reminder:

Utility is the value we assign to money.

You don’t value 100€ the same way if you have 200€ in your account as when you have 2,000€. Same money, different utility.

Everyone has their own utility function, but most of us share some general patterns. And these patterns have huge implications for how we deal with risk.

Securing Gains

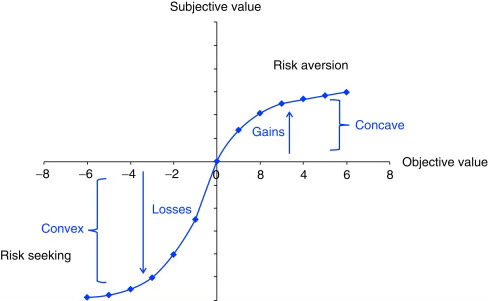

For most people, utility grows slower as we have more money—economists call this a concave utility function for gains.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

I offer you two deals:

Tomorrow I give you 50€.

Tomorrow we flip a coin.

If it lands heads, you get 110€.

If it lands tails, you get nothing.

Most people pick the sure 50€. That’s because we’re risk averse: we prefer a guaranteed profit over an uncertain one, even if the uncertain one has a higher expected value.

Risk aversion is the tendency to prefer certain outcomes over uncertain ones, even if the uncertain ones have a better expected value.

Fearing Losses

But when losses enter the picture, something strange happens.

Let’s try another question:

What would you choose?

Lose 900€ for sure.

A 95% chance to lose 1,000€ (and a 5% chance to lose nothing).

Now, most people pick the gamble. They become risk seeking.

Why? Because the chance of losing nothing feels huge compared to the extra 100€ you might lose. Losing 900€ already hurts so much that losing 1,000€ doesn’t feel much worse.

The pain of losing 900€ is stronger than 95% of the pain of losing 1,000€.

This flip—risk averse for gains, risk seeking for losses—is one of the key insights of prospect theory.

Where Things Get Tricky

Prospect theory summarizes this behavior with an S-shaped utility curve— concave for gains, convex for losses.

But when probabilities get tiny, things change again.

Dreaming Big

Imagine this:

I offer you two options:

Get 120€ now.

A 1-in-1,000 chance to win 100,000€.

Most people go for the gamble. The logic is the same as why we play the lottery: without a ticket, you can’t win; with a ticket, at least there’s a chance.

As Kahneman puts it:

“A lottery ticket is the ultimate example of the possibility effect. Without a ticket you cannot win, with a ticket you have a chance, and whether the chance is tiny or merely small matters little.”

This is the possibility effect: our minds overweight very small probabilities, making rare events feel more likely than they are.

Whereas the concavity of the utility function pushes us to be risk averse and prefer sure outcomes over uncertain ones, the possibility effect pulls in the other direction and makes us be risk seeking.

When facing unlikely but life-changing gains, the possibility effect makes us risk seeking—the opposite of our usual behaviour for gains.

Fearing the Worst

Now flip the situation.

Would you rather:

Lose 110€ now.

Take a 1% chance to lose 10,000€.

This one sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Every time you buy insurance—for your phone, car or home—you are choosing the small, certain loss over the very unlikely large one.

If you do the math, the gamble (option 2) usually has a better expected value (and expected utility!). Yet most of us pick the sure loss. Why?

Again, the possibility effect. Our brains overweight that tiny 1% chance of catastrophe. Even if the math says it’s irrational, the feeling of safety is worth paying for.

In other words, we’re not buying financial protection—we’re buying peace of mind.

It doesn’t matter how small our chance of a big loss is—what matters is that there is a chance.

Conclusion

When we face uncertainty, two psychological forces pull us in opposite directions.

The shape of our utility function makes us risk averse for gains and risk seeking for losses.

The possibility effect makes us overestimate small probabilities, becoming risk seeking for unlikely gains and risk averse for unlikely losses.

Together, they explain why we both play the lottery and buy insurance.

You might play because you’ve fallen for the possibility effect—or simply because dreaming is fun. You might buy insurance because you overvalue that 1% risk—or because you genuinely want peace of mind.

Either way, the point isn’t to change how you act. It’s to understand why you act that way—and to make sure you’re the one choosing, not your biases.

I'm definetely dominated by my risk aversion 😂😂 great post!!