The St. Petersburg Lottery: A 300-Year-Old Puzzle That Will Change How You Think About Risk and Value

Why Mathematicians Say You Should Pay Any Price For This Lottery—But No Sane Person Would Pay More Than €20

This is The Curious Mind, by Álvaro Muñiz: a newsletter where you will learn about technical topics in an easy way, from decision-making to personal finance.

What if I told you there's a new lottery you could play this Christmas?

Before you roll your eyes at yet another lottery scam, hear me out: this one is different. This lottery was invented by one of history's greatest mathematical minds, and for 300 years it has confused economists, philosophers, and mathematicians.

I'm going to show you this lottery, let you play it, and then ask you one simple question: how much would you pay to play?

Christmas Lotteries

Every Christmas, numerous countries around the world play their version of the Christmas lottery.

The prizes are mouth-watering. The Spanish Christmas lottery gives away a total of €2,702M; and if you happen to win El Gordo—the biggest prize—you get €400,000 for each décimo (€20) that you play. The Lotteria Italia has a much smaller total pool (around €21M), yet the first prize rises to an astonishing €5M.

Any sane person would like to win El Gordo or the Lotteria Italia. And, indeed, millions of people pay the €20 that it costs to buy a décimo, or the €5 that it costs to play the Lotteria Italia.

Now here’s the catch. Despite its large prizes, you’d probably not play the Spanish Christmas lottery if the prizes were the same but you had to pay €100 for each décimo. It wouldn’t be worth the price.

But what if I showed you a lottery that mathematically should be worth any price—yet no one would pay more than €20 to play?

The St. Petersburg Lottery

This Christmas, imagine the city of St. Petersburg hosting the strangest lottery you've ever heard of.

Instead of drawing numbers, in St. Petersburg they toss a coin. Here’s how it works:

If tails comes up on the 1st toss, your prize is €2.

If tails comes up on the 2nd toss, your prize is 4€.

If tails comes up on the 3rd toss, your prize is 8€.

And so on—doubling each time.

The game continues until the first heads appears, at which point you collect your prize and go home.

Go try it! You can play the St. Petersburg lottery here.

Now here’s my question for you:

The Paradox

If you try playing the St. Petersburg lottery a few times, you won’t be too impressed with the prizes.

Half of the time you get paid only €2. Only around 6% of the time you’ll get a prize of 32€ or more. And the odds decrease exponentially:

You get more than €100 only 1.5% of the time

You get more than €1,000 only 0.2% of the time

To equal El Gordo and get €400,000, you’ll need to play this lottery over 260,000 times!

The St. Petersburg lottery was invented by the Swiss mathematician Nicolaus Bernoulli around 1713. According to Bernoulli himself:1

Any fairly reasonable man would sell his chance, with great pleasure, for ten euros.

I’m guessing most of you will be willing to pay somewhat in the range €5-20 to play this game, just as Bernoulli suggested.

But here is the shocking truth:

On average, the St. Petersburg lottery will pay you infinite money.2

The expected payoff of the lottery is infinity, thus you should be willing to pay any amount of money to play it!

The fact that we are willing to pay only ~€10 in a game that has an expected value of infinity is known as the St. Petersburg paradox. Let’s explore why this lottery feels worth much less than its mathematical value suggests.

Solution #1: It’s About Utility, not Euros

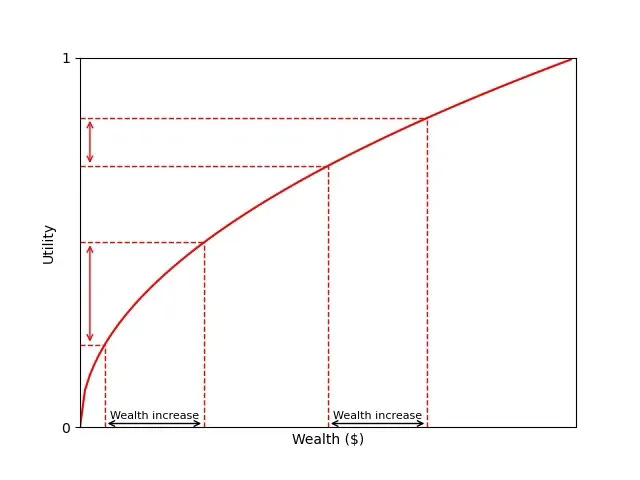

One solution—interestingly, due to Nicolaus’ cousin Daniel Bernoulli—involves utility theory.

We explained in an old post that utility theory is the mathematical theory that explains the value we assign to money. The same €1,000 doesn’t have the same value to someone who has €100 in savings as someone who has €10,000.

The more money we have, the less we value each additional unit.

It looks something like this:

Instead of asking “What is the expected value of the St. Petersburg lottery?”, Daniel Bernoulli’s utility theory says we should ask “What is the expected utility gain from the St. Petersburg lottery?”.

Using a (natural) logarithmic utility, here’s what we get:

A person with €1M in savings should pay up to €20.88 to play this game.

A person with €1,000 in savings should pay up to €10.95.

A person with €2 should borrow €1.35 and pay up to €3.35.

This makes sense: the likely outcomes of the St. Petersburg lottery (winning a small amount of money) are a significant wealth increase for someone with €2, making it profitable for them to risk a high percentage of their savings, but not for someone with €1M.

Solution #2: Our Brain Rounds Down to Zero

Another explanation, due to Nicolaus himself, is that we neglect sufficiently small probabilities.

There is a chance that you’ll get a prize of over €1M—but its likelihood is 1 in 524,288 (you need to play 524,288 times on average to see such prize). Nicolaus argued that we humans perceive such tiny probabilities as literally zero.

In other words, Nicolaus’ point is that, although the game states that we play until we get a heads (and at that point we take the prize), we humans perceive the game effectively as:

Toss a coin until the first heads appears, but at most you’ll toss it X times.

After a point, we just perceive the outcome to be impossible.

If our brain unconsciously caps the game at, say, 20 tosses, the expected value drops from infinity to just €20—which matches our intuition perfectly.

What the St. Petersburg Paradox Teaches Us

The St. Petersburg paradox reveals a profound truth: human decision-making isn’t only about mathematics—it’s about psychology, risk perception, and the subjective value of money. Whether it’s Daniel Bernoulli’s utility theory or Nicolaus’s probability neglect, both solutions tell us the same thing: we’re not irrational for refusing to pay €1,000 for this lottery. We’re human.

So this Christmas, when you see those lottery tickets, remember: the expected value isn’t everything. Sometimes, the smartest bet is the one that lets you sleep at night—even if the math says otherwise.

In Case You Missed It

Bernouilli’s original game dealt with ducats instead of euros, and started with 1 ducat instead of 2. Thus, Bernouilli’s original quote was “any fairly reasonable man would sell his chance, with great pleasure, for twenty ducats.”

Why? Because there's a 50% chance of winning €2, a 25% chance of winning €4, a 12.5% chance of winning €8, and so on. The expected value is: (0.5 × €2) + (0.25 × €4) + (0.125 × €8) + ... = €1 + €1 + €1 + ... = ∞.

Never liked the lottery scam, now I like it even less 😂👏🏽