Framing Effects: Why Your Moral Values Might Be Inconsistent

The Same Problem, Two Opposite Decisions

This is The Curious Mind, by Álvaro Muñiz: a newsletter where you will learn about technical topics in an easy way, from decision-making to personal finance.

Have you ever made two completely opposite decisions about the same problem—simply because it was presented differently? Don't worry, you're not alone. In fact, even experts fall into this trap regularly.

The way information is presented to us has a profound effect on how we process it and act on it. This phenomenon, called the "framing effect," reveals something puzzling about human decision-making: our choices often depend less on facts and more on how those facts are framed.

The Asian Disease Problem: A Classic Experiment

Consider this fascinating decision-making scenario, designed by psychologists Kahneman and Tversky to study how framing affects our choices:

Scenario 1

Imagine that the United States is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

If Program B is adopted, there is a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved.

Now consider this alternative scenario:

Scenario 2

Imagine that the United States is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

If Program C is adopted, 400 people will die.

If Program D is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die.

Take a moment to decide which option you'd choose in each scenario before reading on.

Inconsistency of Choices

If you're like most people, you chose Program A in the first scenario and Program D in the second.

But here's the shocking truth: these choices are logically inconsistent!

Why? Because the programs in both scenarios are identical—just described differently:

Program A and Program C are the same outcome: 200 people live, 400 die

Program B and Program D are the same outcome: 1/3 chance everyone lives, 2/3 chance everyone dies

So why do we make different choices? It all comes down to framing.

How Framing Shapes Our Decisions

Our choices are dependent on the way information is presented to us.

In the first scenario, the options are presented as "gains" or "wins":

We start with a mental baseline of everyone dying

Program A offers a certain gain (200 people saved)

Program B offers a risky gamble (potentially save everyone or save no one)

When dealing with gains, we tend to be risk-averse—we prefer the sure thing.

In the second scenario, the same options are presented as "losses":

We start with a mental baseline of everyone living

Program C guarantees a loss (400 people die)

Program D offers a chance to avoid any loss (though with risk)

When facing losses, we become risk-seeking—we'll gamble to avoid a sure loss.

If presented as a win we go for the sure thing; if presented as a loss we gamble. As Kahneman puts it:

"Risk-averse and risk-seeking preferences are not reality-bound. Preferences between the same objective outcomes reverse with different formulations."

Real-Life Threats: Experts Also Get It Wrong

This isn't just an academic exercise. When researchers presented these same scenarios to public health professionals—the people who make decisions about vaccines and other health policies—they fell into the same trap.

Let that sink in: the experts who determine public health strategy can be influenced by simple changes in how options are presented, not by the actual outcomes.

Framing and Moral Judgments: Helping the Poor while Favouring the Rich

The following is another great example of the inconsistency caused by framing effects. I now realise that many of my political and economical ideals might have been completely illogical!

Scenario A

A government wants to promote families having more children. To do so, families with more children will pay less taxes: there is a baseline tax for having no children, and for each additional child, a family will receive a tax reduction.

Most people will be opposed to this idea. The idea of the favouring the rich with a larger reduction is completely unacceptable.

Now consider this alternative:

Scenario B

A government wants to promote families having more children. To do so, families with more children will pay less taxes: there is a baseline tax for having two children, and having fewer than this will result in a tax increase.

Here, most people are again opposed to this idea: penalising the poor more than the rich is completely unacceptable.

But guess what: these preferences are logically contradictory!

Why Our Moral Intuitions Fail Us

Let's work through a concrete example:

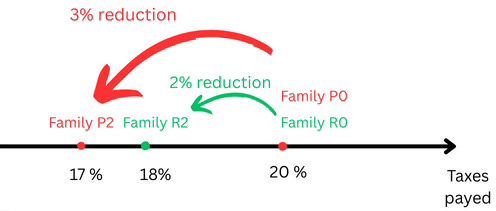

Imagine two families with no children—one rich (Family R0) and one poor (Family P0). Both pay taxes of 20%.

Now consider two additional families, each with two children—one rich (Family R2) and one poor (Family P2).

The government’s aim to promote families having more children translates into Family R2 paying less taxes than Family R0, and similarly Family P2 paying less taxes than Family P0.

According to our response to the first scenario, we believe the tax reduction for Family P2 (compared to P0) should be at least as large as the reduction for Family R2 (compared to R0). For example:

Rich families: R0 pays 20%, R2 pays 18% (2% reduction)

Poor families: P0 pays 20%, P2 pays 17% (3% reduction)

Now consider this instead from the point of view of the 2-children families:

Rich families: R2 pays 18%, R0 pays 20% (2% increase)

Poor families: P2 pays 17%, P0 pays 20% (3% increase)

If we want to favor the poor more than the rich, we necessarily (want to) penalise them more than the rich!

Rethinking Our Moral Judgments

Our intuitive, fast-responding System 1 (as Kahneman calls it) delivers an immediate response to questions about fairness: "when in doubt, favor the poor."

Yet, examples like the one above show that this simple moral rule does not produce logical results, generating contradictory answers to the same problem. As Kahneman puts it, and as sad as it may sound:

"Your moral feelings are attached to frames, to descriptions of reality rather than to reality itself."

What Do You Think?

Now that you understand how framing affects your judgments:

Share your thoughts in the comments! Have you ever noticed yourself making inconsistent choices because of framing?

In Case You Missed It

The Limits of Democracy: What Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem Reveals about Fair Elections

How You Can Make Better Choices (Spoiler: Self-Interest Fails)

Infinity and Beyond: How Some Infinities Are Bigger Than Others

It's amazing how we are so easy to manipulate by something so simple as how we frame things! (And how unaware we are of it... 😰)