The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable #BookReview

Nassim Taleb's Guide to Dealing with an Unpredictable World

This is The Curious Mind, by Álvaro Muñiz: a newsletter where you will learn about technical topics in an easy way, from decision-making to personal finance.

What if I told you that the most significant events in your life and in world history were, by definition, impossible to predict?

That's the fascinating premise of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's 'The Black Swan', the most thought-provoking book I've read this year.

In a world plagued with forecasting, planning, and predicting, I believe Taleb's work is a must-read. Through a combination of philosophy, statistics, and psychology, he reveals why our understanding of randomness is fundamentally flawed—and how this misunderstanding shapes everything from financial markets to personal success.

What is a Black Swan?

The central idea of the book (as its title suggests) is that of a Black Swan. Taleb defines a Black Swan as an event with three key attributes:

"First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second it carries an extreme impact […]. Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concept explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable."

The financial crisis of 2008, Hitler’s rise to power and the subsequent world war in the 1930’s, the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 90’s, the rise of the Internet, the COVID-19 pandemic…they are all examples of Black Swans: unexpected, extremely consequential and explainable a posteriori.

Note that, in retrospect, we now think that all these events were somehow predictable—that it was only a matter of time before they happened. This is precisely the third property of a Black Swan: we now think it was explainable and predictable (see the narrative fallacy below), but it certainly was not before it happened.

Think about it: if the 2008 financial crisis was truly predictable, would investors have continued inflating the bubble right until it burst? Are we really smarter today, or are we just benefiting from hindsight?

Why We Miss Black Swans

The Error of Confirmation

We naturally seek evidence that confirms our existing beliefs rather than looking for contradicting evidence: this is the error of confirmation.

However, Taleb argues that we can get much closer to the truth by finding negative instances than positive ones—also known as a negative empiricist approach.

Consider this example: if you believe your friend John is not a criminal, watching him commit no crime for years doesn't prove your belief. All you can say is that there is no evidence that he is a criminal.

On the other hand, a single criminal act immediately disproves your belief—now there is evidence that he is not lawful.

This asymmetry has profound implications: we know what is wrong with much more confidence than we know what is right.

Yet, we keep looking for evidence of what we believe is right!

Absence of evidence (observing cases that agree with our hypothesis) is very different from evidence of absence (observing a single case that contradicts our hypothesis).

The Narrative Fallacy

Humans are storytelling creatures. We instinctively create logical narratives to explain random sequences of events, making the world appear simpler and more predictable than it actually is.

We’ve talked about something similar when discussing the Linda Problem. There, we showed that adding more details to a story—making it more causally explainable—lead us to believe it was more likely, despite that being mathematically impossible.

This inherent bias to create stories is what Taleb and others call the narrative fallacy.

When we read a successful person's biography, we create a coherent story of how their talent and decisions led inevitably to their success. This satisfies our need for causality, but dramatically underestimates the (huge) role of chance (more on this below).

The Problem of Silent Evidence

History shows us only the winners—the successful writers, philosophers, and entrepreneurs who made it to the top. What we don't see are the thousands of equally talented individuals who failed along the way.

Taleb argues that, while someone like Gabriel García Márquez was certainly brilliant, his Nobel Prize wasn't just about skill—luck played a crucial role. This is hard for us to accept because we want to believe success comes from merit alone.1

The math is simple and reveals our flawed understanding of randomness. The probability that any specific writer will achieve García Márquez's success is tiny. But with hundreds of thousands of writers working at any given time, the probability that someone will get extraordinarily lucky becomes quite high.

It just happened to be Márquez who won the luck lottery!

I find this idea fascinating—luck is so important in our lifes. I recommend watching this great video by Veritasium if you are still not convinced (Spanish version here).

The reference point argument: do not compute odds from the vantage point of the successful writer/businessman/intellectual, but from all those who started in the cohort.

Two Types of Randomness

Taleb divides randomness into two domains with fundamentally different properties: Mediocristan and Extremistan.

Mediocristan: Where Outliers Don't Matter

In Mediocristan, extreme outliers have minimal impact on the collective.

Imagine measuring the heights of everyone in a football stadium. If you suddenly added the tallest person on Earth to your sample, it would barely change the average—not even a 1cm difference!

Most "physical" attributes belong to Mediocristan: height, weight, caloric consumption per day, life expectancy…

Statistical tools work reliably in Mediocristan because extreme outliers won't skew your results.

Extremistan: Where Single Events Change Everything

In Extremistan, a single outlier can completely dominate the aggregate.

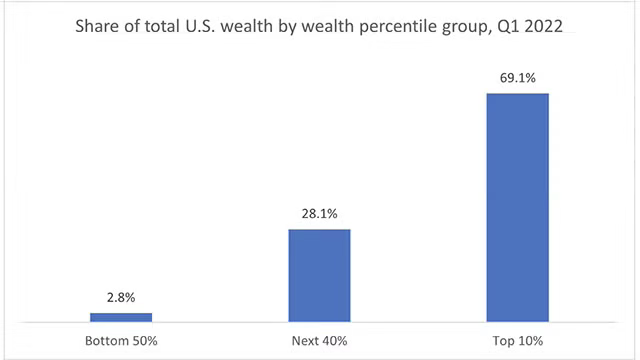

Using the same football stadium example but measuring wealth instead of height: if you added the richest person in the world to the crowd, the average wealth would skyrocket. One outlier completely breaks your statistical model.

Most "social" variables belong to Extremistan: wealth distribution, book sales per author, social media followers, number of speakers per language…

The Essential Problem

We act as we live in Mediocristan, yet many (most) relevant variables in today’s world are indeed part of Extremistan.

We act as outliers are the exception to the norm and they can be safely ignored, yet they are so consequential that they drive the course of history.

Taleb’s Central Thesis: We Simply Cannot Predict

Our Overconfidence Problem

First, there is what Taleb calls “epistemic arrogance”.

This refers to an overconfidence that we have in our knowledge. It has been demonstrated over and over again in experiments: some experiments show that, on average, people are 22 times more confident in their knowledge than they should be!

Note that this does not refer to knowing or not knowing, but rather to being aware of what one does not know.

Paradoxically, more information often makes this worse. The more data we consume, the more patterns we think we see, and the more confident we become in our flawed predictions.

We see random noise and mistake it for information.

The Unpredictability of History

History doesn't evolve gradually but jumps suddenly through Black Swan events. As Taleb puts it, "history does not crawl, it jumps."

Since Black Swans are, by definition, unpredictable and extremely consequential, this means history itself is fundamentally unpredictable.

The Way Forward: Skeptical Empiricism

Rather than false certainty, Taleb advocates for "skeptical empiricism":

Skepticism: Question everything, especially narratives that "make sense".

Empiricism: Prioritize practical experience over elegant theory.

Just because something "makes sense" doesn't mean it works, and something might work perfectly without having a neat explanation!

Taking Advantage of Black Swans

"Put yourself in situations where favourable consequences are much larger than unfavourable ones."

Rather than wasting your time trying to predict Black Swans (if you could predict it, it wouldn’t be a Black Swan), position yourself to benefit from them. This means:

Maximize exposure to positive Black Swans: Seize opportunities that, while unlikely to succeed, would have enormous benefits if they did. This is not an easy task, as you'll need to face many small losses for a long time. However, a single positive Black Swan will compensate all the slow bleeding—in Extremistan, outliers dominate the aggregate.

“Size any opportunity, or anything that looks like an opportunity.”

Minimize exposure to negative Black Swans: Avoid situations that seem safe but could be catastrophic in rare circumstances.

I think this is very insightful. We have a tendency to the opposite: we like ventures that seem not too risky, that sit in the middle of the risk spectrum. Instead, Taleb advocates for a hyperagressive and hyperconservative mentality. keeping the bulk of your investments or actions in the hyperconservative part to limit the effect of a negative Black Swan, yet being hyperagressive in the remaining to get an exposure to the positive Black Swan.

Here's Taleb's financial example:

Instead of putting your money in "medium risk" investments (how do you know it is medium risk? […]), you need to put a portion, say 85 to 90 percent, in extremely safe instruments, like Treasury bills […]. The remaining 10 to 15 percent you put in extremely speculative bets […]. That way […] no Black Swan can hurt you at all, beyond your 'floor', the nest egg you have in maximally safe investments. […] You are "clipping" your incomputable risk, the one that is harmful to you.

This barbell strategy—extremely safe on one end, extremely risky on the other—creates a profile that's resilient to negative Black Swans (if one comes, you lose at most 10/15% of your capital) while has a positive exposure to the Black Swan (if one comes, you can make enormous profit).

Conclusion

The Black Swan offers a profound lesson in intellectual humility. It challenges us not just about what we know, but about what we think we know and what we can know.

History has shown many times how terrible we are at prediction—yet we continue making forecasts with extreme confidence. This overconfidence isn't only a philosophical problem; it has real consequences in our financial systems, public policies, and personal lives.

The inherent unpredictability of our world isn't something to fear but to embrace strategically. As Taleb suggests, we can position ourselves to benefit from positive Black Swans while limiting our exposure to devastating ones. As Taleb puts it:

Knowing that you cannot predict doesn’t mean you cannot benefit from unpredictability—N. Taleb.

In Case You Missed It

What do You want Next?

Note that the opposite happens with negative outcomes: we like to attribute our failures to external events outside our control—to randomness.

Nice thought... Know your limits instead of overestimating yourself so that you can actually maximize your potential!