Two Selves: Living for the Moment or the Memory?

How Peak-End Rule and Duration Neglect Shape Our Perception of Happiness

This is The Curious Mind, by Álvaro Muñiz: a newsletter where you will learn about technical topics in an easy way, from decision-making to personal finance.

What is more important to you, how you live something or how you remember it?

The question is not straightforward by any means. Would you accept an extremely painful surgery operation, if you are guaranteed that the pain will be completely removed from your memory? Would you spend your savings on a holiday that you will enjoy but that you won’t remember at all?

There are two selves inside us, and their interests are very different.

Today we have another topic from Kahneman's Thinking, Fast & Slow. This was, by far, the best book I read in 2024. I plan to do a full book review soon, but this topic was interesting enough to me to make its own post.

Today in a Nutshell

The experiencing self is the one that does our living: it enjoys conversations with friends and dislikes pain.

The remembering self is the one that remembers what we lived: it stores a memory of our holidays and how much we suffered in a surgery operation.

The memories kept by the remembering self are heavily influenced by the highlight and the last moment of an experience: this is called the peak-end rule.

The remembering self does not take into account the duration of an experience: this is called the duration neglect.

While the experiencing self lives with us moment to moment, the remembering self will dictate what we store in memory for the rest of our lives: we act to optimise memories.

Two Selves

Let’s introduce the two selves inside us: the experiencing self and the remembering self.

The Experiencing Self

This is the self that lives life with you as you go.

When you go out with your friends, the experiencing self is the one that is having fun while you dance. The experiencing self has a good time over the holidays: it enjoys the sun, swimming in the morning or hiking up that beautiful mountain. It also dislikes pain or foods that you don’t like.

If you got asked the question "How are you feeling right now?", you would be answering from your experiencing self.

The Remembering Self

On the other hand, we have the memories we keep from an experience.

The remembering self keeps and rates our memories. We only live an experience once, but we can remember it for the rest of our lives. This memory can be positive or negative, and it is the remembering self that handles this storage and retrieval.

If you got asked the question "How would you rate your last holidays, overall?", you would be answering from your remembering self.

Which is the True Self?

When I came across the two selves I thought that our true self is the experiencing self.

This is the self that we should 'optimize' for. For instance, I always thought that it made no sense to obsess over pictures on a trip, to the point that one is not paying attention to the actual moment but just focused on keeping a memory of it.1 Why is your memory so important, if you are not actually living it?

On the other hand, Kahneman proposes some interesting examples in favor of the remembering self. Compare your normal vacation with the following thought experiment:

At the end of the vacation, all pictures and videos will be destroyed. Furthermore, you will swallow a potion that will wipe out all your memories of the vacation. How would this prospect affect your vacation plans? How much would you be willing to pay for it, relative to a normally memorable vacation?

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 389). (Function). Kindle Edition.

As Kahneman puts it, "memories are all we get to keep from our experience of living, and the only perspective that we can adopt as we think about our lives is therefore that of the remembering self."

Interestingly, consider a kind of opposite scenario—instead of living a good memory and not remembering it, living a bad memory and not remembering it:

For another thought experiment, imagine you face a painful operation during which you will remain conscious. You are told you will scream in pain and beg the surgeon to stop. However, you are promised an amnesia-inducing drug that will completely wipe out any memory of the episode. How do you feel about such a prospect?

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 390). (Function). Kindle Edition.

Kahneman thinks that most people would be remarkably indifferent to the pain of the experiencing self. While I agree that a vacation without memories would be not worth the same to me, I actually don’t agree with this! The sole idea of suffering intensively, whether I remember it or not, is repulsive to me.

What do you think?

Odd as it may seem, I am my remembering self, and the experiencing self, who does my living, is like a stranger to me.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 390). (Function). Kindle Edition.

Living vs experiencing

We have so far discussed cases of experiences without memories. This is clearly not what happens in (most of) real-life: we do remember what we live. But, even when we keep memories, there are common conflicts between the two selves.

Let me summarise the main point:

Optimising for a good experience need not lead to an optimal memory.

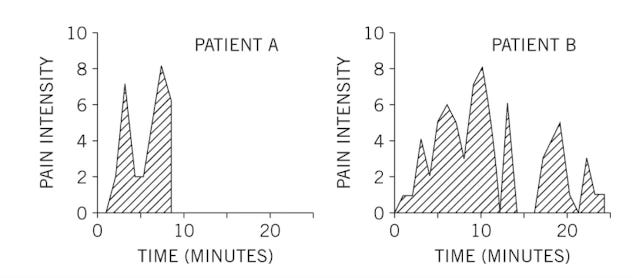

This has been studied in the literature, and the results are clear. For example, a study done in the 1990s followed 154 patients while going through a surgery operation without anaesthesia. Every 60 seconds they were asked to indicate their level of pain at that moment on a scale from 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (intolerable pain). Here are the results for two of the patients:

Seen from the outside, it is very clear that Patient B had a worse experience. The first part of the surgery was very similar to that of Patient A, but after that Patient B had to suffer for another 15 minutes.

Patient B’s pain was that of Patient A, plus some extra pain.2

After the surgery was finished, patients were asked to rate "the total amount of pain".

Can you guess who rated their surgery as more painful? Patient A.

Two Forces Behind Memory

A statistical analysis of the pain profile of those 154 patients, together with their post-rating of the surgery pain, revealed two main forces that dictate how we will remember an experience.

Peak-End Rule

The peak-end rule can be summarised as follows:

You will store a memory as the average of its peak moment and its end.

Our remembering self condenses a whole experience into its highlights and lowest points, looks at what happened at the very last moment and judges the experience accordingly.

We are familiar with this in other aspects of life. A great relationship with your ex-girlfriend can be ruined by a bad breakup. A nice vacation where you got robbed will not be remembered as positive.

Highlights and the end are what goes to memory.

Duration Neglect

This can be summarised as:

The duration of an experience has no effect whatsoever on the memory we will store.

A person who lives a happy life for 20 years will rate their life as equally happy as a person who lives a happy life for 25 years—despite the second person having lived happy for longer. A patient’s surgery length will be irrelevant to their judgment of it, and they will instead focus on what happened at the very end and at the worst moment.

A Moral Dilemma

The conflict between the experiencing and the remembering self poses moral dilemmas for policy makers, doctors and many other professionals.

Should we improve a person’s experience or the memory they will keep from it?

Imagine you are a physician, and you have to choose between a surgery procedure that will lead to a pain profile as that of Patient A, or one that will lead to that of Patient B.

If the objective is to reduce patients’ memory of pain, lowering the peak intensity of pain could be more important than minimizing the duration of the procedure. By the same reasoning, gradual relief may be preferable to abrupt relief if patients retain a better memory when the pain at the end of the procedure is relatively mild.

If the objective is to reduce the amount of pain actually experienced, conducting the procedure swiftly may be appropriate even if doing so increases the peak pain intensity and leaves patients with an awful memory.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (pp. 380-381). (Function). Kindle Edition.

Kahneman thinks people would choose the first option—what do you think?

Conclusion

Whether we like it or not, the remembering self dictates how we approach life. Let me finish with a quote from Kahneman that is worth pondering:

Confusing experience with the memory of it is a compelling cognitive illusion—and it is the substitution that makes us believe a past experience can be ruined. The experiencing self does not have a voice. The remembering self is sometimes wrong, but it is the one that keeps score and governs what we learn from living, and it is the one that makes decisions. What we learn from the past is to maximize the qualities of our future memories, not necessarily of our future experience. This is the tyranny of the remembering self.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow (p. 381). (Function). Kindle Edition.

My question for you:

Is your goal to live or to remember?

In case you missed it

Profit vs. Risk: What Betting Games Teach Us About Human Decision-Making

New Year, New Goals: 7 Science-Based Practices to Set and Achieve Goals in 2025

What do you want next?

There is a separate issue of most of us not even going back to check those memories, at least not as often as we thought we would when taking the picture.

Essentially, we are defining the "total pain" of a patient as the shaded area under the patient’s pain curve (remember your integrals from high school? They are useful!).

Yo que tengo memoria de pez, tengo que elegir sin duda el yo que experimenta. De hecho, muchas veces recuerdo experiencias por lo que me cuentan otras personas que las vivieron conmigo. Si me quedo con el yo que recuerda podría inventarme totalmente buena parte de mi pasado. Uy, pues no estaría mal jejejeje

Very interesting, as always! I think the key is finding balance between actually enjoying what you're doing and making memories that you can look at later on. I don't see a point of taking 1000 pictures if when you look at them all you remember is you taking pictures. I think it would be better to take a phew that help you remember who you met, how you felt or how much fun you had the time that you were NOT taking those pictures! PS: I'm currently reading the book haha can't wait for your whole book review to see if it's worth cointinuing it! 😏